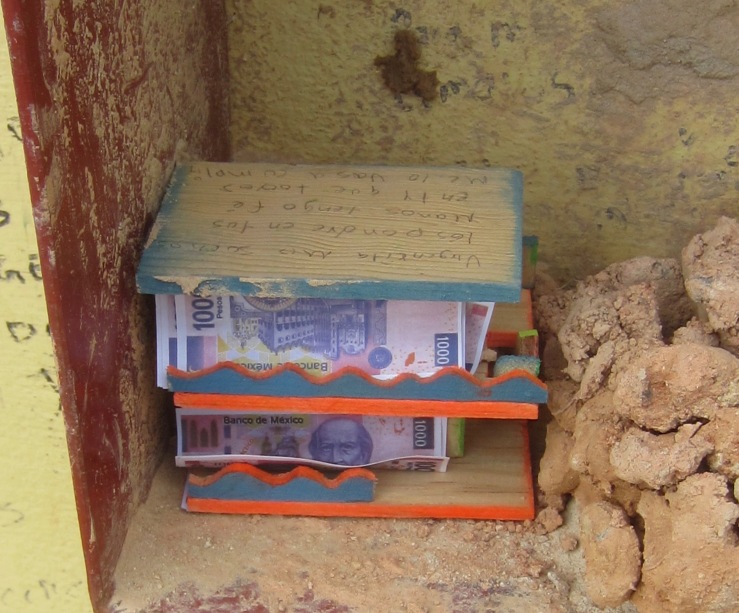

In my archival work, visits to Juquila, and interviews with devotees, the dynamic of taking offerings to the shrine, and bringing home devotional items purchased there has remained a constant. Groups and individuals fill the trees and open spaces around the pedimento with banners and tokens of their gratitude. Many individuals leave chunky votive candles in one of several chapels expressly designed for this purpose. Supporting these endeavors, a warren of stalls outside the shrine make use of every possible inch of space to display the rich array of devotional merchandise.

It is important not to just think of the offerings and items purchased as mere souvenirs. In this I concur with the perceptive analysis offered in Frank Graziano’s recent book, “Miraculous Images and Votive Offerings in Mexico.” Although I can’t do justice to Graziano here, his emphasis on devotions as a complex realm of narration is very helpful. In simplest terms, devotees essentially tell the story of their lives, trips to the shrine, personal hardships, and prayers granted through their saga of belief and commitment to the Virgin of Juquila. In other words, personal histories, testimony of Juquilita’s miraculous intercession, and the powerful role of the items offered and items carried home are interwoven into a single personal narrative: each devotee continually writes and rewrites their own life story as they chart their life of devotion over time. In a sense, life is infused with transcendent significance in the process.

Last week I interviewed Doña Mila, and witnessed this dynamic in action. She describes growing up in the countryside working alongside her parents and 10 siblings, and a childhood where relatives made the trip to Juquila when time and meager finances allowed. Economic necessity forced her to leave her pueblo 40 years ago, and make her living cooking and cleaning in other people’s homes. Nonetheless, she sustained an abiding devotion to the Virgin of Juquila, and has visited the shrine seven or eight times. She attests to several miracles granted by the Virgin. First, as a young woman she received her help in calming a difficult romantic attachment and painful heartache. Years later, an uncle took a special candle from her pueblo to Juquila to help her with a painful, disfiguring skin condition. Doña Mila asserts that at the precise time it was lit at the shrine the problem began to disappear. And, she notes, the image from Juquila brought back by this uncle remains prominently on the family home altar. The Virgin also, she claims, helped her find a way to build her own room connected to her parents’ home. More recently, she has sought and received Juquilita’s help in curing a dear friend of cancer. In addition to these stories, Doña Mila’s retelling of visits to Juquila in buses full of likeminded women, or in friend’s cars, is both her chronicle of devotion and a chronicle of her most important relationships. As Graziano points out, histories of devotion tend to turn back to the emotion-laden, lived experiences of devotees. Ostensibly the protagonist is the miraculous image, but what emerges is also a kind of devout autobiography.

Perhaps my favorite part of Doña Mila’s testimony was her description of a recent trip to Juquila. Like so many others, she took a candle and offered it to Juquilita. However, she noticed that workers at the shrine periodically collected pilgrim offerings and threw them away. They really do pile up after a while, she admits. Doña Mila prayed by her burning candle for a time, and then told Juquilita that instead of having her candle tossed out she would take it home and finish burning it by the image on her altar.